When Paul Burston first met the people of Mishkeegogamang, a remote northern Ontario reserve near Pickle Lake, the First Nations community was struggling with the negative impacts of unemployment, isolation and poverty.

Initially, Burston and volunteers from the congregation at his church in Tottenham responded with emergency supplies, food and clothing, but they also began to build relationships.

They provided summer programs and activities for children, worked side-by-side with residents, and were there to see a rebirth of pride in the community, and the building of new homes and community facilities.

They became not only donors, but partners.

Out of that grew the True North Aboriginal Partnership, a not-for-profit organization set up to connect a number of charities with the people in remote northern communities, identifying needs and creating sustainable solutions in a partnership with the First Nations people for housing and food security.

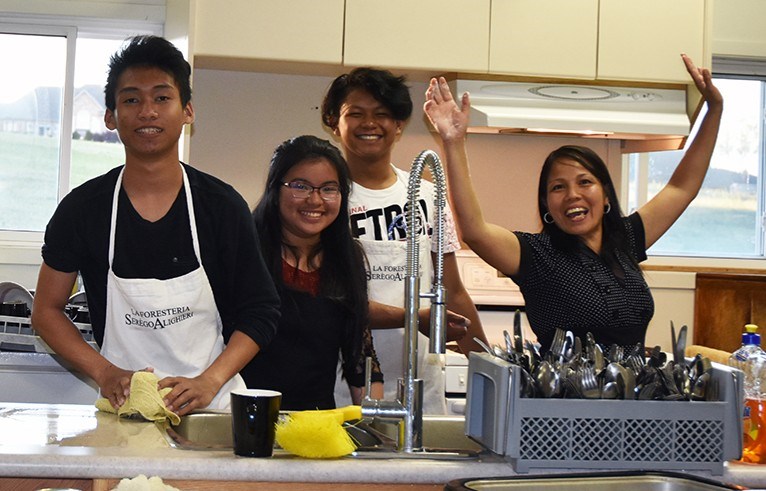

On National Indigenous People Day on Thursday, Green Valley Alliance Church in Bradford West Gwillimbury — now the home church for Burston and his volunteers — hosted a fundraising dinner and auction for True North Aboriginal Partnerships and the people of Mishkeegogamang.

Approximately 100 people attended the dinner, cooked by volunteer chefs Laurie Stellato and Barbara Vaughan and their team of volunteers, and bid on items in live and silent auctions. The event raised more than $5,000.

Guest speaker Ron Stewart, a land surveyor since 1978 who has worked on First Nations land claims, shared his experiences.

He explained the area of southern Ontario bounded by the Great Lakes has always been known as The Dish or The Bowl, and the 17th-century Dish with One

Spoon peace treaty between the Anishinaabe, Mississaugas and Haudenosaunee peoples was an expression of the importance of preserving that resource.

“We all eat out of the dish, all of us who live in this territory, with one spoon. We have to make sure the dish is never empty,” he said. There are no knives at the table, only spoons “to keep the peace.”

It is an agreement and a bond that has been extended to every newcomer to arrive in the area. Everyone is invited to eat out of the dish, and preserve the lands and waters to ensure it is never empty.

Stewart contrasted that understanding with the conditions facing First Nations people in the past 150 years: residential schools, the change to the Indian Act in 1927 that made it illegal for Indigenous communities to retain a lawyer without going through the Department of Indian Affairs (repealed in 1951), the pollution of waterways, and the flooding of First Nations lands without permission or consultation.

“I didn’t even know there was such a thing as residential schools,” Stewart said.

But when he was working on Big Grassy reserve in 1997, he said a co-worker shared his childhood experiences of being sent away, beaten for speaking Ojibwa, and running away twice, only to be returned to residential school by his parents.

Stewart said he learned First Nations people could not vote until 1962.

Communities affected negatively by the construction of dams and hydro projects, facing starvation, sent pleas for help but were ignored, he said.

Elders spoke of the ripping apart of families by the residential schools and the “big scoop” in the 1960s.

“Sometimes it’s pretty hard to take. I didn’t even know this stuff existed — and here it is in Ontario,” said Stewart.

He has since worked with many Indigenous communities on their land claims, noting the Ontario government is finally settling some of those claims through negotiation — largely “because they got hammered every time they were in court.”

And, he said, things are changing through education, investment and the exposure of the abuses.

The Department of Indian Affairs has been split in two departments to deal with land claims and with services more efficiently.

The struggle continues for many in Indigenous communities, “but they are a strong people,” Stewart said.

The key to reconciliation, he said, is to build relationships based on respect.

Bradford West Gwillimbury has been involved in building relationships with Mishkeegogamang, through Burston and the late Jack MacFadden.

MacFadden’s Coats for Kids grassroots organization helped provide warm winterwear and food for the northern community, where local prices can be as high as $9.99 for a box of Cheerios and $32 for a container of coffee.

And MacFadden, an educator, created learning opportunities and connections.

The Buy a Book, Share a Book event in BWG provided new books for the Missabey School on the reserve, but also built an appreciation of Indigenous culture.

In recent years, the Grade 8 students graduating from Missabey have been rewarded with a trip “south,” to visit the local community and see the sights in Toronto and Niagara Falls.

“That’s how reconciliation happens,” Burston told Thursday’s gathering.

Burston, who is the president and founder of True North Aboriginal Partnership, noted that visiting Missabey students expressed fears of moving to Thunder Bay for high school — a city where seven Indigenous students have died in recent years, two of them from Mishkeegogamang.

“When they travel outside of their reserve, they’re in a whole new world. They don’t know how to be safe,” Burston said.

By creating friendships in the south, partnerships, and a network of caring, he said, they can be safer and succeed.