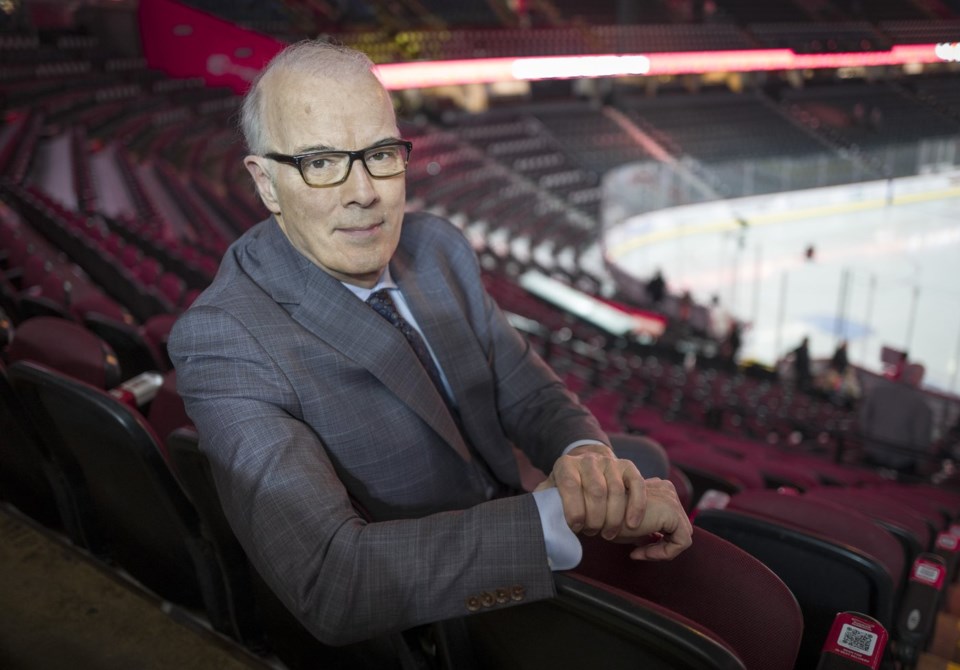

Scott Oake tells stories for a living.

From the Olympic Games to the Stanley Cup finals, the veteran sports broadcaster has witnessed crowning achievements and crushing disappointments. Emotion-packed moments that stick with fans and viewers.

Those tales of success, failure, triumph and heartbreak have never been his own. He's simply a conduit.

The story Oake tells in his book published this week — "For the Love of a Son: A Memoir of Addiction, Loss, and Hope" — was the toughest to share.

"Very difficult," Oake said in an interview. "Very, very difficult."

Bruce Oake died in 2011 at age 25 from an accidental drug overdose after a years-long battle with the scourge of drug addiction.

Scott Oake, a longtime "Hockey Night in Canada" personality, details his son's life and death, a devastated family's pain, and the decision to tell Bruce's story with the goal of helping others.

"Bruce's life and his struggle are laid out in chronological order," Oake said. "Very difficult to tell."

Tell it, however, is exactly what Oake has done. There was no other way.

"You have choices when you lose a child," he explained. "Our choice was to give voice to our grief in hopes what happened to us wouldn't happen to another family."

Oake and his late wife, Anne, started to share Bruce's story. It was a graphic presentation. Nothing was left out. The book is no different.

That includes the raw, gritty details. But it's also the story of a Winnipeg boy and his family. Bruce had friends. He had dreams. There were good times with younger brother Darcy, achievements that made his parents proud, summers at the cottage. All cruelly taken.

"There was always a group of people wanting to tell us their stories of loved ones struggling," Oake said. "That was our impetus to continue."

The plan was to raise money for a non-profit residential treatment facility in Winnipeg after seeing the options available during Bruce's struggles.

"If we didn't have the courage to talk about Bruce in public," Oake said, "we'd never get anywhere."

That's what the Bruce Oake Recovery Centre required.

Scott Oake quipped his and Anne's greatest skill in seeking financial support through a foundation in their son's honour was "having lunch and asking for money."

The long road saw nine separate municipal votes — "Pretty sure that's a civic record," Oake mused — and plenty of community criticism.

That pushback, along with the media coverage, helped their cause.

"Every time we were in the news people rallied," Oake said. "It was worth it … as tough as it seemed at the time."

The 50-bed, all-male facility opened in May 2021. Bruce's ashes sit in an urn placed in the building's entryway — to honour a son and make clear what's at stake.

Oake visits the centre often and speaks with participants in the 16-week program, although he has nothing to do with its day-to-day running.

"I'm smart enough not to inject myself into the process," he joked. "If I did, it would be closed in a week."

The goal is to not only help people with substance use disorders but also educate the wider population.

"Addiction doesn't discriminate," Oake said. "It can come for anybody, regardless of socio-economic class. It is a disease. People who are addicts deserve a chance to get healthy, to get their lives back."

Anne Oake isn't here to see the fruits of their labour. The centre's matriarch, as Oake calls her, died of an illness shortly after it opened.

Fundraising for the Anne Oake Family Recovery Centre, a facility for women in Winnipeg, is already halfway to its $25-million target.

"A dagger that she's not here," Oake said. "But her spirit endures."

Scott Oake was among 88 people appointed to the Order of Canada last month.

"Builders of hope for a better future," Gov. Gen. Mary Simon said in a statement. "They broaden the realm of possibilities and inspire others to continue pushing its boundaries."

Oake said Bruce and Anne, while proud, would probably be laughing.

"The first thing they'd think is, 'Why can't you just shut up?'" he said before turning serious. "I wish I never had to answer that question. I wish they were here."

Oake has a quiet word for Bruce every time he walks past his son's urn. He will do the same with Anne at the new facility, but added playfully: "I want to be careful people don't think this whole thing is an Oake mausoleum project."

Scott Oake didn't want to become an author. He would have preferred to stay in his lane, continuing to tell athlete stories.

Life had other plans.

"A kid like any other," Oake said of Bruce. "He had goals, dreams, could have been anything. He got sick. He tried hard, it claimed his life.

"But his journey was about more than addiction."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Jan. 21, 2025.

"For the Love of a Son: A Memoir of Addiction, Loss, and Hope." Scott Oake with Michael Hingston. Simon & Schuster, 237 pages, $26.99.

Joshua Clipperton, The Canadian Press