Underwater secrets from another century await off the shores of Centennial Beach, but you’ll have to mask up.

Located approximately 80 metres out from the beach — and about 10 metres down — lies the wreck of the J.C. Morrison, a sidewheel paddle vessel that plied the waters of Lake Simcoe for three short years before catching fire and sinking in 1857.

In her day, the 150-foot long steamboat, which was constructed in 1854 at Belle Ewart, was something to behold.

The ship was fitted by the prestigious Toronto furniture company, Jacques and Hay, according to the authors of Beautiful Barrie, who add the inside was decked out in velvet sofas, mirrors and stained glass.

“The carved and plush interior made the Morrison the most palatial ship ever to navigate the lake,” authors Su Murdoch and Brad Rudachyk write in their book chronicling Barrie's history. “Regular service commenced in 1855, making it the first (ship) to daily circumnavigate the lake, returning passengers to Toronto on the evening train.”

While it now lies submerged and broken after 164 years, the J.C. Morrison is still accepting guests.

“The wreck is one of the most popular dive sites in Lake Simcoe,” Chris Sproule, of Simcoe Diving, tells BarrieToday.

He descends on the wreck about 40 to 50 times a year, either with student divers or experienced divers, especially on Fridays when members of the Simcoe Scuba Club suit up and head down.

“We introduce many divers from all over Ontario and beyond to the sport and to the site,” he says of the Saunders Road business in south-end Barrie, which he operates with his wife, Lorraine.

“One of the most exciting aspects of the wreck to see is one of the remaining paddle wheels,” Sproule says. “It’s quite large, measuring 20 feet in diameter with wooden blades approximately four-feet long by two-feet wide. It lies on its side just to the east or port side of the wreck.”

Also interesting to see is what he refers to as the stanchions, the support system that held the two paddle wheels in place.

“It still lies vertically and rises from about 25 feet up,” he says.

Getting to the dive site has its challenges, not all of which are under the surface.

“One of the biggest hazards to diving can be the boat traffic above,” Sproule says. “Many boats come close to the dive site, sometimes not knowing or seeing the (bright orange) dive buoys that divers tow along.”

Then you’ve got the sharp bits of the wreck itself along with zebra mussels, crayfish and the boat’s encrusted overhead beams, which are a falling hazard.

Poor visibility can sometimes make finding and seeing the wreck especially challenging, he says.

“Unfortunately, most divers want to dive it when the lake is the warmest (July to September), but often the visibility is poor — only five to 10 feet — with high levels of algae and weeds.”

The best time to dive with the best visibility is when the lake is cold in late fall or early winter, Sproule says.

“Once the lake cools off, the algae dies off and the weeds flatten down on the bottom. Some of my clearest dives have been just before the lake freezes," he says.

“Sometimes divers get lucky in the spring and have a few dives that are quite clear after the winter particulate settles and the algae and weeds haven’t yet had a chance to grow.”

While COVID-19 has negatively impacted the dive industry globally due to travel limitations, it has renewed an interest in local diving, Sproule says.

“Our calls to guide new divers to the wreck have significantly increased this summer,” he says.

If you get the bug to get under water, Sproule says there are two big things to keep in mind: safety and preparation.

“Newcomers to the sport often think it’s physically easy to scuba dive,” he says. “While once you are in the water and comfortable with your underwater skills it can be comfortable and relaxing, it can also be quite strenuous to carry around all the required gear outside of the water.

“With diving, the preparation to dive and the proper gear care can take longer than the dive itself.”

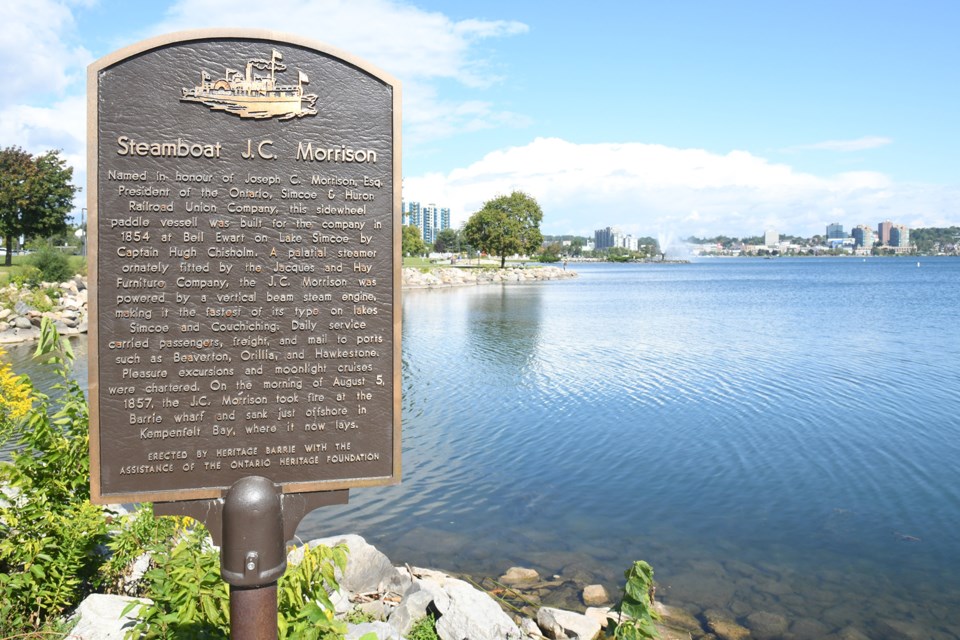

There is a plaque near the Tiffin Boat Launch commemorating the sinking of the J.C. Morrison. The steamboat was named for Joseph C. Morrison, who was president of the Ontario, Simcoe and Huron Railroad Union Company.

The vessel, which chartered "pleasure excursions and moonlight cruises," was captained by Hugh Chisholm.

It was the fastest vessel of its type on lakes Simcoe and Couchiching, the plaque declares, providing daily passenger, freight and mail service to various ports, including Orillia, Beaverton and Hawkestone. The vessel caught fire the morning of Aug. 5, 1857, near the Barrie wharf and sunk not far from shore.