Work to preserve the environment of Ontario’s Far North is overflowing with creativity.

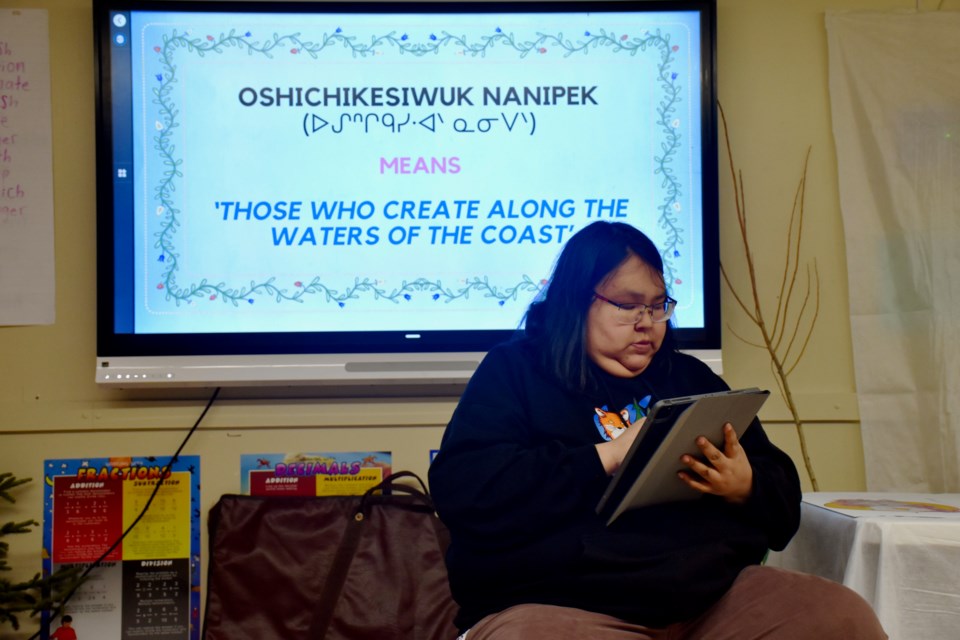

A new artist collective, which goes by Oshichikesiwuk Nanipek, is empowering Omushkego artists to be stewards of their homelands and stewards of the breathing lands, says program manager Galen Boulanger.

“The whole idea with this is that when we talk about management of lands, we’re talking about the future of homelands for people in this area and that relates to the cultural practices and tradition and spirituality of the people. It’s more than just science, it’s more than just conservation and how we think of it in a Western idea. It’s inclusive of culture, inclusive of spirit,” he says.

In mid-February, the collective launched its first exhibit in Kashechewan, a Cree community on the James Bay coast about 400 kilometres from Timmins.

A classroom at Francine J. Wesley Secondary School was transformed into an art gallery. John Reuben's oil paintings of grouse and outdoor scenes, the bright and bold work of Betty Albert, a collection of paintings from Shibastik, and more, depicted ways that the artists connect to their land and culture.

“Art is a universal medium. You can walk into the room and you can see the reverence of the land in these pieces. There’s this ability to communicate that is so important and powerful, that I think this is just the beginning,” says Boulanger.

While an artists’ collective isn’t unusual in itself, nanipek is unique in that it falls under Mushkegowuk Council’s lands and resources department.

Specifically, it came about as part of the national marine conservation area (NMCA) project that's working to protect the marine area of James and Hudson Bay.

Tawich — the feasibility study for the NMCA — was formally accepted on Feb. 21. It allows the project to move on to the next steps, with negotiations with Parks Canada expected to start in the spring. The goal is to safeguard a 90,000-square-kilometre area, protect Treaty rights, and secure resources to create jobs.

SEE: Mining, conservation can go hand-in-hand: director

The work of the artists is woven into all aspects. Along with their inclusion in the announcement, the pages of Tawich are decorated with colourful artwork and photographs of artists from Omushkego, which means the strong people and is the name Cree people in the area use to describe themselves.

Messengers of conservation

"My people will sleep for 100 years, but when they awake, it will be the artists who give them their spirit back."

The Louis Riel quote inspired Lawrence Martin, Mushkegowuk's lands and resources director, to involve artists in the organization's two conservation projects; along with the NMCA, they are also working to protect the James Bay peatlands through the project for finance permanence (PFP).

Both projects are significant as the area is the second-largest carbon sink in the world. In simple terms, a carbon sink is a natural environment — in this case, the ocean and peatlands — that absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

The artists, says Martin, are the messengers of conservation.

“Everything we’ve been hearing from the scientists, from traditional elders, land users, it’s all from stories. It’s stories about the sturgeon, about the goose, about the polar bear. It’s all based on stories and what people have experienced over life so that’s why the artists are the storytellers,” he says.

Martin and Mushkegowuk director Vern Cheechoo understand the power of art.

Both are musicians — Martin's even a Juno Award winner. As someone who sells art, Martin has seen the powerful impact it can have on people.

“They capture that spirit of that animal or that bird or that piece of land that they paint. They put so much into it, it comes from their dreams, it comes from their life experiences, it’s very profound," he says, talking about customers being brought to tears connecting with a piece of art.

"So I’m hoping that these artists when they show the work of the conservation work, that they’ll have the same impact on people who will look at their paintings. There’s one there that I saw in the room, I think it was done by Chris Sutherland — Shibastik — and it’s a place that I’ve been to and I knew it right away since I saw it … and everything is as exactly as I saw it."

Validating a dream

The collective is also connecting people to their potential.

No matter where Robin Kioke was positioned during the gathering, there was one constant for the soft-spoken artist. An iPad.

Whether sitting in the hall or the art room next to her work, she was constantly sketching.

After creating for over two decades, new possibilities are surfacing for the Attawapiskat First Nation artist.

Two years ago, she convinced her parents to gift her an iPad for her birthday.

“Before I got the iPad, I was always (using) paper, pens, inks with pencils because it was very hard to get hold of art supplies and very expensive if you do try. So I always stuck to the sketchbook, pencils and … it was always black and white, basically,” she explains.

By attending the inaugural get-together for Omushkego artists last year, she inked her first commission work — designing the nanipek logo.

“I was very excited because it’s just a validation of a dream I had ever since I was a kid,” says Kioke.

The colourful logo showcases Kioke’s love of drawing animals and nature.

The final design features a whiskeyjack surrounded by pink flowers. There’s also a traditional drum that boasts the shoreline of Hudson and James Bay.

Art is helping a mother-daughter duo get in touch with each other, their ancestors and the land.

Adrienne Beaupre and her daughter Christina Bekintis’ paintings are inherently connected to the land, the animals and the ties with the water and moon.

“Art gives voice in a way that words can’t. It's kind of like when you’re out on the land and you’re sitting with the water, that spiritual connection you have, that you can portray that through paintings and it speaks in a way that words can’t. Just kind of like when I have that feeling of being on the land, that connection. I’m able to show it through my artwork,” says Bekintis, a Garden River First Nation member who uses the name Fire Wolf for her artwork.

It was Bekintis who inspired her mom to pick up a paint brush.

“I started painting when I was far from home on the American side and I was missing the connection to the land,” says Beaupre, who goes by Dawn Eagle for her art and is a member of Chapleau Cree First Nation.

A woman performing a pipe ceremony, praying for the land and water, is her first painting. The small canvas was part of the Kashechewan exhibit.

“Where I was living, the rocks and the land looked so much different, which was New York State. (Painting) helped me connect back to the land even though I was far away and then my daughter would guide me online on how to paint,” says Beaupre.

'When you protect that land, you have a place to go'

Janie Kataquapit knows she has a really important role.

An Attawapiskat First Nation member, she creates traditional regalia, paints, and makes dreamcatchers, moccasins and mittens. As a grandmother, she’s working to keep the water and land of Mushkegowuk protected for future generations.

For Kataquapit, who works with Oshichikesiwuk Nanipek, it's a natural connection between art and conservation projects.

“Our way of creating has always been with us because we’re so close to the land. Everything is symbolic so that’s why you see a lot of artists, they come from the spirit, from the heart because for them — the land, the water, the air. We’re all one,” she says.

Kataquapit heard from an elder once about the government saying the land isn't being used.

She likens the vast territory Mushkegowuk territory, which is part of Treaty 9, to a farm in southern areas. It's for animals and plants, except there's no fence around it.

“That’s being preserved, that’s our farm, so when you protect that land, you have a place to go,” she explains.

“The land wasn’t given to us, it was to borrow for our next generation. If we don’t take care of it, we’re not going to have anything. When I think about it, sometimes I feel I get emotional …. that’s how much it means to me,” she says.

A lot of the artists are also hunters, gatherers and harvesters who rely on the land.

“For us, that’s always been our way and that’s also our future, it’s never going to change. For us to keep going we have to protect the future for them. For my role, it’s really important because artists can give a powerful voice — some people can do it in music, storytelling, painting, or even today, people can take advantage of media, just like (Kioke), she’s drawing media. Artists have very powerful voices too, especially when it’s grassroots,” she says.

Along with conservation efforts, Kataquapit wants to see people succeed.

"There’s so much talent there that we would like to see them have their own business going, self-sustaining. And they’re represented and they’re being heard,” she says.

An international affair

In 2023, Mushkegowuk Council brought artists together at a gathering in Timmins.

From there, the collective started to take shape. Nanipek.ca launched earlier this month and features profiles of some of the artists, as well as their work.

Another artists' gathering is being held in Timmins March 25 to 27, with over 100 people registered.

Getting artists the supplies they need and creating a market for their art are part of the next steps for the collective.

As part of the March gathering, Martin says they want to connect artists and trappers.

"The market has dried up — the international fur industry market — but there are still people utilizing fur for products ... from animals and the artists are always the ones using fur or hides and stuff like that. We’re trying to create that connection between the trappers and the artists as a circular marketing opportunity,” he says.

Helping artists make a living doing to their craft is also a focus, and Martin has big city dreams.

"We want to be able to help them establish galleries where they are, and not just in Kash, because the market is limited, but in big cities like Toronto and Ottawa, New York ... so it becomes an international affair. Because our message that we have here is international, it’s global.

"What we’re trying to save under the conservation idea is the breathing lands, the carbon that’s in the second-largest carbon sink in the world, keeping that in tact. If it gets disturbed, it affects the whole world. And all the waters that flow into James Bay and Hudson Bay, if they get disturbed, that also impacts the whole world, so the artists work should be recognized internationally because of that,” he said.

Artists interested in the collective can visit nanipek.ca or email [email protected].