As part of their ongoing battle to stop the Bradford Bypass, environmental groups are urging the provincial government to instead consider changes to local roads that would ease traffic woes with less impact on the environment.

Forbid Roads Over Green Spaces (FROGS), Simcoe County Greenbelt Coalition, Rescue Lake Simcoe Coalition and other local volunteers hosted a third town hall Tuesday evening in East Gwillimbury, following similar events in Bradford West Gwillimbury and Sutton.

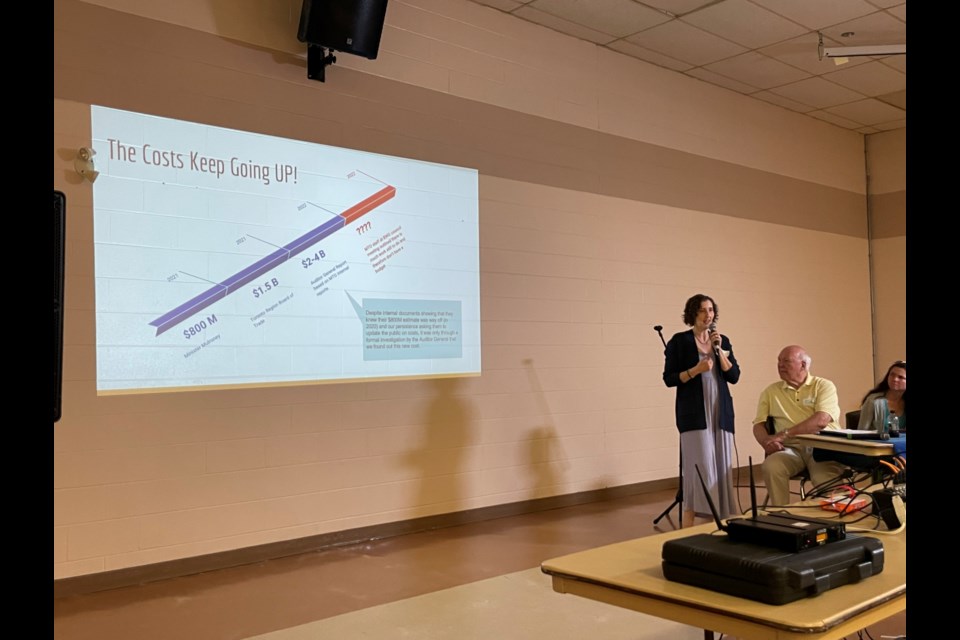

Before moving forward with a project as environmentally harmful as the Bradford Bypass, these groups want to see other roads and routes considered. They don’t think a highway project expected to cost between $2 billion and $4 billion is the best way to spend taxpayer money.

About 25 attendees heard that there are two local solutions that warrant consideration over the 16.3-kilometre four-lane east-west Bradford Bypass that would connect Highways 400 and 404.

Linking Ravenshoe Road to Line 13 and extending Queensville Sideroad to 8th Line, which connects to Highway 88 at 10th Sideroad, would alleviate congestion, said Bill Foster, founder of FROGS.

“Even if the Bradford Bypass is built, there’s a compelling need for a regional road in this area,” he said. “If it’s not built, these are excellent local solutions.”

The groups say regional road improvements would cost 10 per cent of what the Bradford Bypass would cost and allow for funds to be put toward other issues such as nurse shortages, long-term care staffing, and OHIP coverage.

“If we use the $4-billion price tag and divide it by the number of kilometres, this project is going to cost Ontarians a quarter of $1 billion for every kilometre, making it one of the most expensive highways to be built in recent history,” said Margaret Prophet, executive director of Simcoe County Greenbelt Coalition.

With dramatic growth coming to East Gwillimbury and Bradford, even if the bypass is built, local solutions will still be needed to address local traffic congestion, Foster said.

He said the Ministry of Transportation should confirm details regarding how much time the Bradford Bypass would save local drivers, not just "long distance" travellers, driving from Barrie to Oshawa and Keswick to Mississauga, for example.

“The 35-minute savings promised by (Premier Doug) Ford and (Minister of Transportation Caroline) Mulroney for this highway would be very meaningful for long distance travellers. It’s nowhere as important for people who only want to drive through Bradford, especially once local solutions are implemented.”

Foster added that municipal government, not the province, is responsible for intra-municipal transportation.

“(The ministry) policy is to not mix local traffic with long distance traffic,” he says. “Ford and Mulroney are using planned local growth to justify the need for this highway. (The ministry) is focusing on local traffic, a municipal responsibility.”

“They were really only looking for a place where they could put a corridor for a controlled access highway and nothing else,” Foster added. “They included the Bradford Bypass in the Places to Grow Act, which attracted land speculators that we now call developers. Their actions created local rather than long distance travel demands from their sprawling developments.”

The groups contend there have been fundamental traffic needs in the area since Hurricane Hazel hit in 1954, and the province has been pushing for a major highway since the 1970s.

“We’re concerned with the traffic problem ... behind this whole highway idea,” said Claire Malcolmson, executive director of Rescue Lake Simcoe Coalition. “We want traffic solutions that are implementable that aren’t $4 billion and can be demonstrated that they’ll work. We recognize that there are traffic problems that haven’t been dealt with for decades.”

The impact the Bradford Bypass could have on Lake Simcoe is one of the biggest reasons these groups are urging the provincial government to look at more local options. The bypass is expected to cross 13 watercourses, including the East and West Holland Rivers.

Among the other concerns the panel addressed was how adding more highways will impact air quality.

“If you live near a road, traffic is the major source of pollution for you,” said Laura Bowman, a lawyer with Ecojustice. “Highways increase the amount of kilometres travelled, they induce people to drive more. They create car-centred development, development that is far away and it causes people to drive more.”

Referencing studies available through the National Library of Medicine, traffic-related air pollution’s health effects can have lasting impacts on pregnancies, infants, and children.

“Traffic-related air pollution is associated with low birth weight and preterm birth,” said Bowman. “For children who live close to a highway, their lungs don’t develop properly. It’s associated with global premature mortality. The premature mortality risk with a 0 to 100 metre buffer of a major road was 566 per cent higher than for a 301 to 400-metre buffer.”

With the highway not expected to be completed until 2032, this is not a clear and immediate solution, the groups underlined.

“All we’re saying is, as (the Ministry of Transportation) said back in 1993, solve local problems with local solutions,” said Foster. “Do not use long distance solutions because if you do, you’re going to cause major congestion with local and long distance traffic trying to get through on the same road. We don’t need a 16-kilometre $4 billion highway to get local people to the highway, what we do need are solutions now.”