It was a “rainy, drizzly, grey foggy day.”

Sounds like the start of a mystery novel. It was, in fact, part of the introduction to the Crime Writers of Canada panel at the BWG Public Library on Saturday, which was a rainy, drizzly, foggy day.

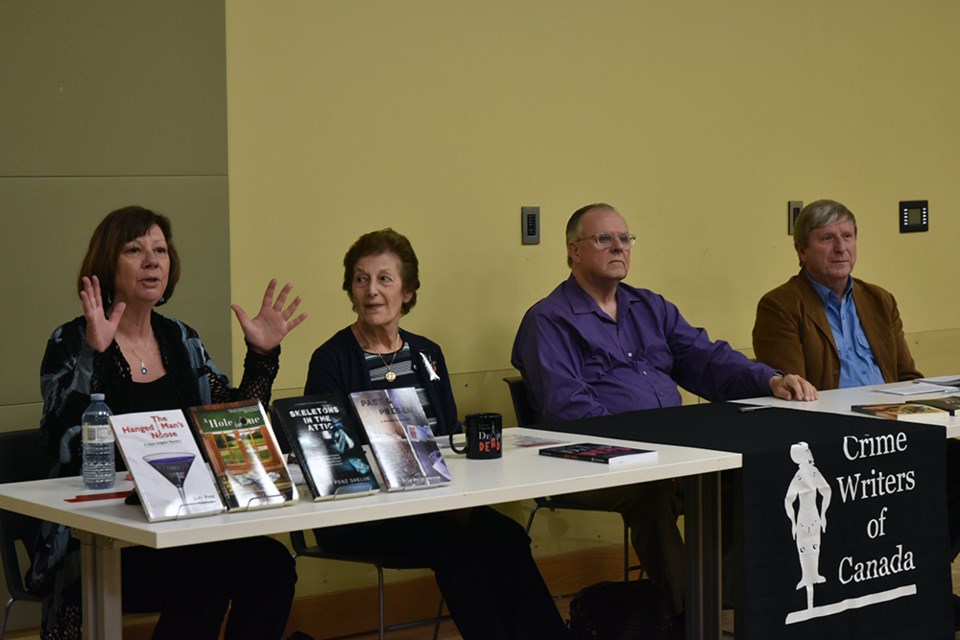

Chaired by mystery writer Judy Penz Sheluk, the panel featured published authors Ken Ogilvie, John Worsley Simpson, and Lorna Poplak, and covered a range of crime-writing styles.

Penz Sheluk described her Glass Dolphin and Marketville mystery series as “amateur sleuth, with an edge.”

Ogilvie writes the Rebecca Bradley “suspense thrillers.”

Worsley Simpson, whose first novel was nominated for a Crime Writers of Canada Arthur Ellis Award, works in the genre of “police procedurals;” his main protagonist is a cop called in to investigate homicides.

And Poplak, author of Drop Dead – The Horrible History of Hanging in Canada, writes non-fiction, about historical crimes.

The questions were probing, the answers enlightening. Not only did the audience – made up of mystery lovers, readers and aspiring authors – learn about the work of each panelist, they were given insight into the process of writing.

Ogilive was asked, “What made you, as a male, decide to write a female protagonist, and a police woman, rather than an amateur sleuth?”

“It was a friendly take-over,” Ogilvie replied, explaining that he had originally planned to have a male protagonist, “six feet tall, 300 pounds." But every time he re-wrote his first novel, “Rebecca’s voice got stronger and stronger… She told the story.”

Penz Sheluk asked Simpson, a former journalist, if he ever based his tales on real police cases.

“No,” Simpson said, pointing out that he only briefly covered a police beat; for the most part, he was an editor for The Globe and Mail, in business. “There were very few murders – some I wanted to commit myself.”

Although not a “how-to” on policing, Simpson said he did try to ensure that the police procedures described in his books are accurate.

“The idea is not to give you stuff that is wrong,” he said.

Poplak was asked how much research it took to write her history of Canada’s 109-year “experiment” with capital punishment.

“Every item, every detail, every single word that went into the book had to be researched,” Poplak said. “My main source was archival newspapers.”

The cases she covered ranged “from the really pathetic and tragic, like Louis Riel,” who spent the night before his hanging on his knees in prayer, to the absurd.

“On the other hand, you get the description of the hangman who spent the night at the prison… snoring like a ‘traction engine’,” Poplak said.

Her book started as an article, written around the time of the Tori Stafford murder. When eight-year-old Tori was abducted, raped,and murdered, newspapers were filled with letters calling for the return of the death penalty.

After reading the letters, Poplak wanted to take a closer look at capital punishment in Canada and started with a biography of ‘Arthur Ellis’, “the most notorious hangman of Canada. That just drew me in.”

Ellis is believed to have conducted over 600 hangings in the UK, Canada and the Middle East during his ‘career’ and the Crime Writers’ Arthur Ellis Award is named in his honour, Poplak noted.

The writers were asked about the settings of their novels.

Ogilvie, who grew up in a small town, sets his work in the small town near Georgian Bay, a “completely created” locale.

Simpson writes about a recognizable Toronto, with obvious precautions.

“If your description is too close to a real person, you could be sued,” he warned. When he had to come up with the name of a crime boss, “I went through phone books to make sure there was nobody of that name.”

But his street names and landmarks are real. “It helps to have a sense of place in the book. It adds a note of verisimilitude.”

Sheluk’s books take place in ‘Lount’s Landing’ and ‘Marketville’ which are inspired by Holland Landing and Newmarket, although there are no real businesses named. Those businesses might not want to be associated with murder, however fictional, she said.

“The best authors make the location a character,” said Sheluk.

“I don’t create my locations, but I do have to recreate them,” said Poplak. “I have to make them pop, bring them alive for people.”

The authors also differed in how they tackled their craft. Sheluk called herself a “pantser. I write by the seat of my pants. When I begin, I have no idea who did it,” she said. “I try to use an outline. That doesn’t work for me. I end up going off-script.”

Simpson is at the other end of the scale. “I’m a plotter,” he said, working out the details of each novel chapter by chapter.

“I think the important thing with a mystery is, you have to figure out how the mystery is going to be solved. If you don’t have a solution, you’ll be wandering around,” Simpson said. “You can’t have something just appear.”

That said, he admitted, “I have an ending worked out, but along the way it may change.”

Ogilvie said he fell somewhere in between, “in transition” from “pantser” to “plotter.”

His first book was written without planning. It was “learn as you go,” he said. “Then you start to realize the mistakes you made.”

Poplak explained that the parameters of her book were set by the premise.

“I began when hanging began, and I stopped when hanging was abolished.” She handled the massive amount of data by “going on the principle of low-hanging fruit… I wrote about the most interesting first.”

And they all had different places to do their writing.

Sheluk writes at home, listening to Talk radio. “I can’t imaging writing in a noisy coffee shop, or even a library where there are other human beings,” she said.

Poplak writes on her computer and at reference libraries, while Ogilvie prefers coffee shops, where he can be inspired by the conversations around him. Simpson writes “anywhere.”

“As a journalist early on, I was used to the clatter of teletype machines, the noise of police radios,” Simpson said. “I could block it out – as long as the person wasn’t saying anything interesting. I often write with music playing. I love jazz.”

And all agreed with Sheluk: “There’s nothing worse than an ending that’s unfair. We do have to layer in those clues… so the intelligent reader can say, I didn’t figure it out but if I had been on my game, I could have.”

The panel answered questions from the audience, then sold and signed their books for their new fans who enjoyed the rainy, drizzly, grey foggy day.