Wild animals move through landscapes to find water, food, shelter, mates and nesting sites, but roads and traffic make it more difficult and dangerous for them. As many countries move to expand their road networks, especially in tropical areas, an increasing number of mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians face the risk of being killed.

Roads and traffic already kill a massive amount of wildlife, which can lead to the loss of local populations, including species that live in low densities or reproduce slowly, like lynx, badgers, porcupines, turtles and owls. This can have cascading effects — interrupting mutually beneficial relationships or rupturing food webs — that can lead to the loss of other species.

Depending on the country, roadkill can range from hundreds of thousands to several hundred million animals annually. According to a recent study, an estimated 194 million birds and 29 million mammals are killed each year on European roads. Some jurisdictions have taken measures to reduce roadkill — the Netherlands and Switzerland, for example, have wildlife fences and passages — but it still is an increasing global concern.

Wildlife fences, installed along the length of the road, reduce wildlife mortality, but they can be controversial. They are often considered unpleasant compared to “cool” wildlife overpasses, because they add to the barrier effect caused by roads in the first place.

We devised a plan for prioritizing roads sections for wildlife fencing to reduce roadkill, based on the identification of roadkill hot spots and cold spots.

Essential, but controversial

It is expensive to install and maintain fencing to prevent animals from dying in traffic. Unless it is relevant to driver safety, transportation agencies have largely neglected to reduce roadkill.

When transportation agencies and wildlife managers are asked about their thoughts on installing fences along roads, many are skeptical and often view them as unpleasant features. In contrast, wildlife overpasses are viewed as “cool.” In reality, however, those “cool bridges” alone do not reduce road mortality.

Recent evidence indicates that road mortality is more detrimental to most wildlife populations than fences. In the majority of cases, fences are more urgently required than wildlife passages. But how long should they be and where is the need most pressing?

Roadkill hot spots

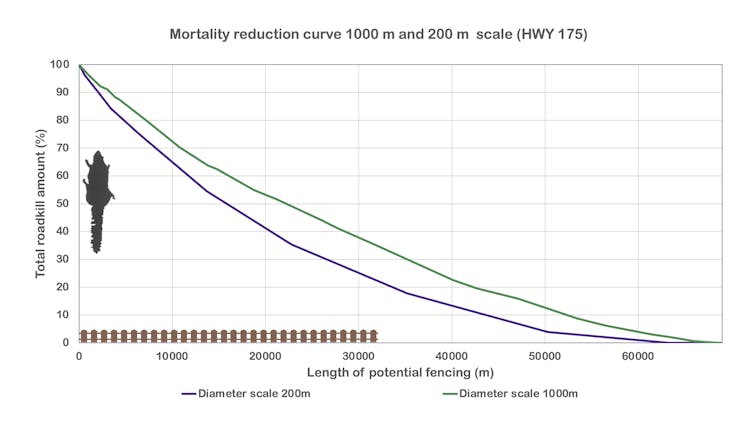

Fencing entire road networks is not realistic. We determined how transportation agencies might prioritize road sections for fencing by using mortality surveys, identifying roadkill hot spots at multiple scales and planning mitigation measures in a methodical way that follows an adaptive-management approach.

Roadkill hot spots can be identified at different scales, which can influence decisions about where fences should be placed. A hot spot at one scale may not be a hot spot at another scale.

We used roadkill data from three roads, one from southern Québec and two from Rio Grande do Sul, in Brazil. The first road cuts through the Laurentides Wildlife Reserve and borders the Jacques-Cartier National Park in Québec. One of the roads in Brazil crosses through two protected areas and runs along the Atlantic Forest Biosphere Reserve, while the other borders slopes of the Serra Geral Mountains and coastal lagoons.

Initially, we thought many sections of short fences could be built near hot spots identified at a fine scale to reduce roadkill. We expected that this approach might also require less total fence length than fencing fewer hot spots identified at courser scales while achieving the same roadkill reduction.

However, animals can move easily around fences that are too short. They may then get killed at the fence ends — an issue known as the “fence-end effect.” The fences need to be long enough to reduce the danger of a fence-end effect.

A few long fences or many short ones?

This trade-off between the use of a few long or many short fences has important implications for biodiversity conservation. Finding the right balance depends on the distances that animals move, their behaviour at the fence, the mortality reduction targets for each species considered and the structure of the landscape near the road.

For example, turtles move across much shorter distances than lynx, and their roadkill hot spots are very localized. Accordingly, many short fences are appropriate for turtles, whereas fences designed for lynx need to be much longer.

After fences have been installed, roadkill hot spots can disappear or shift, and new ones may appear, so road mitigation must be able to adapt. Our step-by-step plan helps transportation managers decide where to place fences, and whether they should be long or short.

Fencing has been shown to be effective and is the most realistic way to decrease roadkill. Wildlife conservationists and transportation agencies should install fences more actively than wildlife passages to reduce the effect of roads and traffic on wildlife populations. Fences also increase traffic safety for drivers.

Thus, given the global boom in road construction on the planet, biodiversity is under rapidly increasing threat and the need to reduce road mortality globally, and to add wildlife fences, is more urgent than ever.![]()

Jochen A.G. Jaeger, Associate Professor, Geography, Planning and Environment, Concordia University; Ariel Spanowicz, MSc student in Environmental Science, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, and Fernanda Zimmermann Teixeira, Postdoctoral researcher, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.